Facts about Puerto Vallarta, Mexico PV Pedia. Puerto Vallarta Pedia is a tourist-oriented municipality and city in the Mexican state of Jalisco, positioned along Banderas Bay on the Pacific Ocean coast. The municipality covers 1,107 square kilometers and recorded a population of 291,839 in the 2020 national census.

Originally established on December 12, 1851, as the fishing village of Las Peñas by settler Guadalupe Sánchez Torres and his family, the area evolved into a port and adopted its current name in 1918 to honor Ignacio Vallarta, a former Jalisco governor. Post-World War II infrastructure investments spurred residential and commercial expansion, transforming it from a modest agrarian outpost into a prominent resort destination by the late 20th century.

The local economy relies heavily on tourism, which employs the majority of workers through hotels, restaurants, and related services, drawing visitors to its coastal beaches, the Malecón boardwalk, and nearby ecological sites like Los Arcos Marine Park. In 2024, Puerto Vallarta’s international airport processed 6.8 million passengers, reflecting sustained growth in air travel arrivals that supports the sector’s dominance. This development has integrated traditional Mexican culture with international influences, though rapid urbanization has strained local resources and infrastructure.

History

Pre-Hispanic and Colonial Foundations

The region encompassing present-day Puerto Vallarta, situated in Bahía de Banderas within the state of Jalisco, was inhabited during pre-Hispanic times by indigenous groups affiliated with the Xalisco kingdom, including communities such as Tintoque, Pontoque, and Tondoroque.[9] These peoples, often identified as Cuyutecos or related to broader western Mexican groups like the Aztatlán culture, exploited the fertile Valley of Banderas for agriculture and sustained small-scale settlements, with archaeological evidence indicating human presence dating back to at least 350 B.C. Nomadic and semi-sedentary tribes occupied the coastal and inland areas, engaging in fishing, maize cultivation, and trade, though the region lacked the monumental architecture of central Mesoamerican civilizations.

Spanish exploration reached the Jalisco coast in the early 16th century amid the broader conquest of western Mexico, with Cristóbal de Olid and Nuño de Guzmán leading expeditions that encountered resistance from local indigenous populations. In March 1525, Francisco Cortés de San Buenaventura, a relative of Hernán Cortés, landed in Bahía de Banderas with a small force, initiating conflicts documented in Spanish records as skirmishes between conquistadors and native warriors. A notable battle in 1524 involved indigenous groups deploying colorful flags or banners leading the Spaniards to rename the bay Bahía de Banderas (Bay of Flags) highlighting early tactical disparities in warfare that favored European firearms and armor over native strategies.

Discover Videos all about Puerto Vallarta – Riviera Nayarit https://promovisionpv.com/puerto-vallarta-youtube-videos-by-promovision/ See what, where, how, adventures, events, memories, meet the Chefs.

Colonial administration integrated the area into New Spain through encomienda systems, where conquered indigenous labor supported Spanish mining and agricultural ventures in nearby highlands, though the coastal zone remained sparsely settled due to persistent native resistance and rugged terrain. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Bahía de Banderas served primarily as an occasional anchorage for shipping goods to support inland silver mines, such as those in San Sebastián del Oeste, rather than as a formal port; missionary efforts by Jesuits and Franciscans aimed to convert locals but faced ongoing hostility, contributing to demographic decline from disease and conflict. These foundations laid the groundwork for later development, with the bay’s strategic location enabling rudimentary trade networks amid the encomienda’s extractive economy.

19th-Century Settlement and Early Development

The settlement of what would become Puerto Vallarta originated in the mid-19th century as a modest outpost amid the rugged terrain of Bahía de Banderas. On December 12, 1851—coinciding with the Catholic feast day of the Virgin of Guadalupe—Guadalupe Sánchez Torres, accompanied by his wife Ambrosia Carrillo and other settlers, established a permanent community named Las Peñas de Santa María de Guadalupe, referring to the area’s prominent rocky outcrops. This founding marked the transition from sporadic indigenous and transient use of the site to organized habitation, driven by the need for a coastal access point in a region isolated by the Sierra Madre Occidental mountains.

Early development centered on its function as a rudimentary port and fishing hamlet, facilitating the transport of goods from inland areas lacking direct sea access. Las Peñas served primarily as a beachhead for loading and unloading supplies destined for or exported from nearby mining operations and agricultural enterprises in towns such as San Sebastián del Oeste, Talpa de Allende, and Mascota, where silver mining and crop cultivation generated regional economic activity. Subsistence fishing supplemented local livelihoods, with the Cuale River providing freshwater resources amid a landscape dominated by mangroves and crocodiles, though permanent structures remained few, consisting mainly of basic adobe homes clustered near the river mouth.

By the late 19th century, the settlement had grown modestly to include several dozen families engaged in these extractive and maritime support roles, but it retained a peripheral status within Jalisco, overshadowed by more established ports like Manzanillo. No formal municipal recognition occurred until the early 20th century, reflecting its slow evolution from a supply depot to a viable community, constrained by limited infrastructure and vulnerability to natural hazards like floods from the Cuale.

20th-Century Transformation into a Resort Destination

In the early 20th century, Puerto Vallarta functioned primarily as a small port for exporting agricultural products like corn, beans, and tropical fruits, with connectivity enhanced by the construction of a railroad linking it to interior Mexico, which facilitated trade but did not yet spur significant population growth or tourism.

By the 1930s, modest tourist visitation emerged, with a few domestic and international visitors returning annually for the area’s serene beaches and landscapes, though access remained challenging without modern roads or air links.

The 1950s marked preliminary infrastructure advances, including the establishment of a basic airstrip around 1954 that supported small commercial flights from Guadalajara and other regional hubs, enabling limited elite tourism while the town retained its fishing village character with a population under 12,000.

A transformative catalyst arrived in 1963 with the filming of John Huston’s The Night of the Iguana in nearby Mismaloya, featuring Richard Burton and Ava Gardner, alongside Elizabeth Taylor’s presence amid her affair with Burton, which drew global press coverage and highlighted the region’s exotic appeal.

The film’s 1964 release catalyzed a tourism surge, shifting perceptions from remote hamlet to desirable getaway and prompting initial hotel constructions as visitor numbers rose sharply.

Federal and state government efforts in the late 1960s amplified this momentum, culminating in the 1970 inauguration of Licenciado Gustavo Díaz Ordaz International Airport on August 20 following construction from 1966 which accommodated jet aircraft and international arrivals, alongside the El Salado wharf opening that year to handle cruise traffic.

These developments fueled a construction boom in resorts and amenities through the 1970s, reorienting the economy from subsistence activities toward service-based tourism, with hotel occupancy and foreign investment expanding rapidly.

Post-2000 Expansion and Modern Challenges

Following the turn of the millennium, Puerto Vallarta experienced sustained population growth, with the metropolitan area expanding from approximately 300,000 residents in 2000 to 556,000 by 2023, driven primarily by tourism-related migration and economic opportunities. This demographic surge paralleled a boom in visitor numbers, as foreign tourist arrivals, which peaked at 872,710 in 2000, evolved into total annual visitors exceeding 6 million by 2023, including a record 4.46 million documented arrivals that year, reflecting robust recovery and expansion post-COVID.

Infrastructure developments underscored this expansion, including major investments in hospitality, with billions of dollars committed to new luxury hotels and renovations in the mid-2020s to accommodate growing demand.[35] The Licenciado Gustavo Díaz Ordaz International Airport underwent significant upgrades, such as the construction of Terminal 2, projected to double capacity, alongside $290 million in modernization efforts over five years to handle increased air traffic. Complementary projects included highway expansions, free bike-share systems, and shuttle buses to enhance mobility amid rising visitor volumes.

Modern challenges have tempered this growth, particularly vulnerability to natural disasters, exemplified by Hurricane Patricia in October 2015, the strongest recorded in the Western Hemisphere with winds up to 215 mph, which brushed Puerto Vallarta’s coast, causing temporary airport closures, flooding, and infrastructure strain but limited direct urban damage due to its landfall in sparsely populated terrain inland. Ongoing preparations for active hurricane seasons, such as dredging 16 rivers and canals in 2025 to mitigate flooding, highlight persistent risks exacerbated by coastal geography.

Water supply constraints represent a core strain from rapid urbanization and tourism, with the city’s systems producing about 1,200 liters per second—fully consumed daily amid high seasonal demand leading to frequent shutoffs, leaks, and saline intrusion into aquifers from overexploitation near the ocean. Efforts to stabilize supply, including well connections and conservation campaigns, continue, though broader regional droughts since 2024 have intensified shortages.

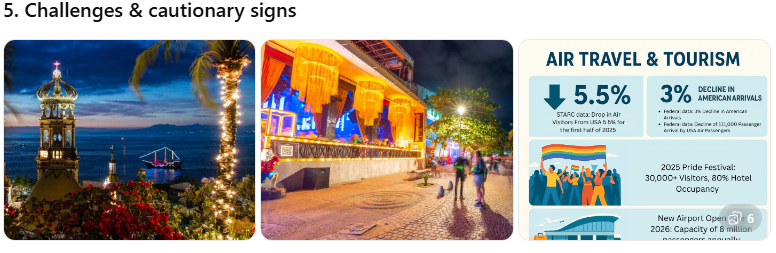

Security issues, while less severe than in other Mexican regions, include sporadic drug-related violence tied to national cartel activities post-2006, though Puerto Vallarta maintains low rates of tourist-targeted crime, with assaults comprising about 31% of reported violent incidents but minimal impact on the resort economy. Recent tourism dips, such as a 2025 decline in U.S. visitors, alongside concerns over corruption and inadequate public transport, further challenge sustainable development.

Geography and Environment

Physical Location and Topography

Puerto Vallarta municipality occupies the Pacific coastline of Jalisco in western Mexico, at the southeastern terminus of Bahía de Banderas, a bay extending approximately 42 km along the coast and shared with Nayarit to the north. The municipal seat, the city of Puerto Vallarta, is situated at coordinates 20°37′00″N 105°13′00″W, with an elevation averaging 7 meters above sea level along the shore. The municipality borders Nayarit to the north and west, Tomatlán municipality to the south, and extends eastward into inland Jalisco territories, covering a total land area of 1,300.7 km².

The topography features a narrow coastal plain of alluvial deposits and sandy beaches fringed by the bay, dissected by rivers such as the Cuale, which flows through the city center and forms an island park, and the Pittillal to the north. Eastward from the shoreline, the terrain ascends abruptly into the rugged foothills and slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental, with elevations rising to over 1,000 meters within the municipal boundaries, covered in tropical dry forests, mangroves, and steep river gorges. This mountainous backdrop constrains horizontal urban expansion, channeling

development along the 40 km of coastline and contributing to a diverse landscape of beaches, estuaries, and elevated jungle habitats.

Bahía de Banderas itself represents a submerged tectonic graben, offering a deep, sheltered harbor up to 30 meters in depth near the city, which has historically supported fishing and now tourism-related maritime activities. The surrounding topography includes rocky headlands like Los Arcos to the south and expansive wetlands, creating a varied coastal ecosystem influenced by the interplay of marine and terrestrial features.

Climate Patterns and Natural Hazards

Puerto Vallarta exhibits a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw), characterized by high temperatures year-round and a pronounced wet-dry seasonal cycle driven by the interplay of Pacific Ocean influences and the North American monsoon. Average daytime highs range from 28°C to 32°C (82°F to 90°F), with nighttime lows rarely dipping below 20°C (68°F), resulting in minimal annual temperature variation of about 4.4°C (7.9°F). The dry season, from November to May, features low humidity and scant precipitation, typically under 30 mm (1.2 inches) per month, making it ideal for tourism. In contrast, the wet season spans June to October, coinciding with the Pacific hurricane period, when monthly rainfall surges to 200–400 mm (8–16 inches), concentrated in intense afternoon thunderstorms that account for over 80% of the annual total of approximately 1,500 mm (59 inches).

These patterns stem from warm sea surface temperatures fueling convective activity in summer, while winter northeasterly trades suppress rain. Relative humidity averages 70–80% during the wet season, exacerbating heat indices above 35°C (95°F), though coastal breezes provide some moderation. Long-term data indicate a slight upward trend in extreme rainfall events, potentially linked to regional warming, though direct attribution remains debated amid natural variability.

Natural hazards primarily include tropical cyclones, flooding, and seismic events, amplified by the city’s coastal topography and proximity to the Middle America Trench. The Pacific hurricane season (May 15–November 30) poses risks, with storms like Hurricane Kenna (2002), which made landfall 100 km north and generated 200 km/h winds and 500 mm rains in Puerto Vallarta, causing widespread flooding and infrastructure damage. Direct hits are infrequent—roughly once per decade—but indirect effects, such as Hurricane Patricia (2015), brought 300–500 mm rains, triggering landslides in surrounding Sierra Madre del Sur slopes. Flooding recurs during wet-season deluges, overwhelming rivers like the Cuale and low-lying zones, with historical events displacing thousands and eroding beaches.

Earthquakes, stemming from the Cocos Plate subduction, are felt periodically, though major destructive quakes are rarer than in central Mexico; the 1985 Michoacán event (magnitude 8.0) registered intensities up to VII in Jalisco, damaging older structures. Tsunami risk exists from offshore quakes, with paleotsunami evidence indicating rare inundations up to 5 km inland, but no significant modern events recorded locally. Mitigation efforts, including early warning systems and zoning, have reduced fatalities, yet rapid urbanization on floodplains heightens vulnerability to compound hazards like cyclone-induced surges.

Environmental Pressures from Urbanization and Tourism

Urban expansion in Puerto Vallarta, fueled by tourism-driven real estate development, has encroached on natural habitats including mangroves, dunes, and marshes, often bypassing environmental safeguards. This has resulted in the conversion of approximately 1,340 hectares of land to urban use, contributing to deforestation rates that outpace natural tree loss in surrounding mountains.

Habitat fragmentation from these activities threatens biodiversity, with endemic species facing extinction risks due to loss of forest cover—totaling 93,408 hectares regionally—and altered ecosystems from proximity to tourist zones, which disrupt wildlife behavior and migration patterns. Agriculture and livestock expansion have further deforested 6,493 and 19,700 hectares respectively, exacerbating soil erosion and reducing rainwater retention critical for preventing urban flooding.

Water resources are under severe strain from population growth and seasonal tourism surges, with municipal systems producing about 1,200 liters per second, frequently inadequate to meet demand during high season when tens of thousands of visitors arrive. Inadequate precipitation has depleted aquifers, leading to chronic shortages and infrastructure failures reported at around 83% for drinking water systems in mid-2025 surveys.Coastal pollution arises from inadequate wastewater treatment, with hotels discharging untreated effluent directly into Banderas Bay, as observed near sites like Grand Park Royal in late 2024, harming marine ecosystems and posing health risks. Rainy season runoff has elevated fecal enterococci levels, rendering beaches such as Camarones, Mismaloya, and Cuale temporarily unsafe for swimming as of July 2025.

Beach erosion accelerates from tourism infrastructure like seawalls and hotel construction, which disrupt natural sediment flows and degrade shorelines in this high-development coastal zone. These pressures collectively amplify vulnerability to natural hazards, underscoring the causal link between unchecked growth and ecological degradation.

Demographics and Urban Growth

Population Dynamics and Migration Patterns

The population of the Puerto Vallarta municipality stood at 291,839 according to Mexico’s 2020 national census, with a near-even gender distribution of 50.1% men and 49.9% women. This marked a 14.1% rise from the 2010 census figure of approximately 255,800, equating to an average annual compound growth rate of about 1.3%. Such sustained expansion, surpassing Mexico’s national urban averages, stems from a combination of modest natural increase and net in-migration, as fertility rates in resort-driven locales like Puerto Vallarta hover below replacement levels while economic pull factors draw newcomers.

Migration patterns reflect the city’s tourism-centric economy, attracting internal flows from other Mexican states particularly rural areas in Jalisco, Nayarit, and Michoacán for jobs in hospitality, construction, and services, alongside international arrivals seeking retirement or lifestyle advantages. In the five years prior to the 2020 census, documented inflows totaled over 2,000 recent migrants, predominantly from the United States (1,570 individuals), Canada, and Venezuela, with primary motivations cited as improved living conditions (692 cases), family ties (670), and legal relocation (256).These figures, derived from INEGI surveys, understate cumulative international settlement, as Puerto Vallarta sustains an established North American expatriate community estimated at around 35,000 Americans, many retirees concentrated in coastal enclaves.

Net migration remains positive, fueling urban densification and seasonal swells from “snowbirds” Northern retirees wintering in the area—though official data emphasize economic causation over speculative booms, with internal labor mobility offsetting any out-migration of locals amid rising costs. This dynamic has intensified post-2010, correlating with tourism recovery and infrastructure investments that amplify the city’s appeal as a migration magnet.

Socioeconomic Composition and Inequality

Puerto Vallarta’s socioeconomic composition is characterized by a predominantly working-class population engaged in tourism-related services, supplemented by internal migrants from other Mexican states and a smaller but visible community of international expats, primarily retirees and remote workers from the United States and Canada. As of 2020, the municipality’s population stood at 291,839, with recent migrants including 1,570 from the United States and 195 from Canada over the prior five years, though expat residents are estimated in the low tens of thousands and concentrated in upscale neighborhoods like Marina Vallarta and Zona Romántica. The economy’s heavy reliance on hospitality and retail employs a significant informal sector, mirroring Jalisco state’s 46.9% informality rate in early 2025, where many workers in beach vending, small-scale services, and unregistered tourism gigs earn below formal wages amid seasonal fluctuations. Average monthly salaries in the region hovered around 5,710 Mexican pesos in the first quarter of 2025, reflecting low-wage service dominance that sustains a modest middle class of property owners and mid-level managers while limiting upward mobility for the majority.

Income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient of 0.32 in 2020, is lower than Mexico’s national average of approximately 0.39-0.45 in recent years, indicating relatively moderate distribution compared to other regions, though stark decile gaps persist with the lowest income quintile averaging 16,900 pesos quarterly versus 179,000 pesos for the highest. This metric captures a tourism-driven duality: affluent expat investments and high-end developments inflate property values and local business revenues, benefiting a narrow elite, while the bulk of residents depend on precarious, low-productivity jobs that expose them to economic volatility from tourism downturns, such as those during the COVID-19 period. Poverty affects 32.1% in moderate conditions and 3.29% in extreme as of 2020, with 27.4% vulnerable to social deprivations like limited access to healthcare and education, and 10.7% at risk from income instability figures that underscore how seasonal employment and informal work exacerbate household precarity despite overall growth. Spatial segregation amplifies these divides, with wealthier enclaves in the hotel zone contrasting poorer outskirts, where infrastructure lags and remittances from tourism trickle unevenly.

Household incomes averaged 62,800 pesos quarterly in 2020, sufficient for basic needs in a low-cost locale but strained by rising real estate prices fueled by foreign demand, which displaces lower-income locals and fuels gentrification debates. Efforts to diversify beyond tourism remain limited, perpetuating a composition where service workers form the socioeconomic base, expats inject capital but few permanent jobs, and inequality manifests less in raw Gini terms than in access to quality employment and housing stability.[79] This structure, while enabling Puerto Vallarta’s prosperity relative to inland Mexico, highlights causal vulnerabilities: overdependence on volatile visitor spending sustains inequality by concentrating gains among asset holders rather than broadly elevating wages or formalizing labor.

Urbanization Challenges and Infrastructure Strain

Rapid urbanization in Puerto Vallarta, fueled by tourism expansion and inward migration, has imposed significant strain on local infrastructure, outpacing development in critical areas such as water supply and waste management. A June 2025 survey by Mexico’s National Urban Public Opinion Survey (ENSU) indicated that 83.2% of residents identified failures and leaks in the drinking water system as a primary urban issue, reflecting chronic shortages exacerbated by overexploitation of aquifers and seasonal tourist influxes. The local aquifer faced a deficit of 5 million cubic meters as of June 2024, attributed to overdevelopment, population growth, and inadequate precipitation depleting underground sources. This scarcity intensified during high season, with officials redirecting supplies in April 2025 to cope with temporary population surges, highlighting the causal link between tourism-driven demand and resource depletion.

Traffic congestion and road maintenance further compound infrastructure pressures, with 80.7% of residents criticizing inadequate public transit and 80.4% reporting potholes as pervasive problems in the ENSU survey. The city’s road networks, designed for lower volumes, struggle with daily flows impacting up to 116,000 commuters, particularly in tourist corridors like the Malecón area, where limited parking and urban density amplify bottlenecks. Waste management systems have similarly faltered under growth demands; a shift to every-third-day collections in December 2024 led to visible overflows, prompting a September 2025 trial of daily pickups with 10 new trucks to achieve citywide coverage, as mandated for service provider Red Ambiental. Sewage and drainage upgrades lag, with excess high-rise construction threatening to overwhelm networks, potentially collapsing services amid ongoing gentrification that displaces low-income households through rising housing costs.

These strains stem from uncoordinated jurisdictional growth across Puerto Vallarta and neighboring Bahía de Banderas, where floating populations push capacity limits during peak periods, as noted in analyses of tourism’s resource impacts. While initiatives like the 80%-complete Puerto Vallarta Junction interchange aim to mitigate congestion, persistent gaps in regulatory enforcement and investment underscore the tension between economic reliance on visitors and sustainable urban scaling.

Economy

Tourism as Economic Driver

Tourism dominates Puerto Vallarta’s economy, contributing approximately 84% to the municipal GDP according to the city’s 2025 Tourism Intelligence Report, which analyzed direct and indirect dependencies on visitor-related activities such as hospitality, retail, and transportation. This heavy reliance stems from the city’s appeal as a beach resort destination, drawing international visitors primarily from the United States and Canada, alongside domestic Mexican tourists, who fuel spending on accommodations, dining, excursions, and souvenirs. In 2023, the sector generated 41.322 billion pesos in income while attracting 6.04 million total visitors, including 4.46 million arrivals via air, land, and sea.

The influx sustains formal employment for over 148,000 workers as of 2023, a 6.5% rise from 139,000 the prior year, with roles concentrated in hotels, restaurants, tour operations, and retail sectors that expanded amid post-pandemic recovery and infrastructure investments. Average per-visitor expenditures, such as 14,620 pesos during the 2024 summer season, amplify this impact, yielding localized spillovers like 3.5 billion pesos from that period alone across hospitality and services. Early 2024 data further illustrates momentum, with January-to-May tourism inflows producing 31.8 billion pesos, equivalent to about one billion U.S. dollars at prevailing exchange rates, underscoring seasonal peaks driven by winter escapes from northern climates.

Puerto Vallarta’s tourism engine has shown resilience and growth, closing 2024 with record hotel occupancies nearing full capacity during holidays and exceeding prior benchmarks in visitor volume, though precise annual totals remain aggregated with Riviera Nayarit metrics in national reporting.[96] This performance positions the city as Jalisco state’s leading tourism contributor, bolstering regional GDP while highlighting vulnerabilities to external factors like air connectivity and currency fluctuations, yet empirical trends affirm its role as the primary growth catalyst amid limited industrial diversification.

Real Estate and Investment Trends

Puerto Vallarta’s real estate market has experienced significant growth since the early 2010s, fueled primarily by international tourism and demand from North American buyers seeking vacation homes and retirement properties. Foreign investors, particularly from the United States and Canada, account for a substantial portion of transactions, drawn by the city’s coastal appeal, direct flights from major U.S. cities, and favorable climate. This influx has driven property values upward, with beachfront areas commanding premiums due to limited supply and high rental potential from short-term vacationers.

Average sale prices in primary regions, including downtown and hotel zones, reached approximately USD 550,000 in 2024, with condos averaging around USD 500,000 as of late 2024. Beachfront properties in Puerto Vallarta traded at an estimated MXN 130,000 per square meter in 2025, positioning the city as one of Mexico’s pricier coastal markets behind Los Cabos and Tulum. Year-over-year price appreciation slowed in 2025 amid rising inventory, which increased 33% by September, shifting leverage toward buyers and extending average days on market. House sales rose 23.7% year-to-date through July 2025, though median prices dipped in some segments due to higher financing costs and peso-dollar fluctuations.

Foreign ownership is restricted under Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution, prohibiting direct land acquisition within 50 kilometers of the coast—the “restricted zone” encompassing Puerto Vallarta. Buyers must utilize a fideicomiso, a bank-held trust granting beneficial use and control for up to 50 years, renewable, with setup costs typically 1-2% of property value plus annual fees. This structure mitigates risks but introduces dependencies on banking stability and potential regulatory changes, as evidenced by occasional fideicomiso disputes in Mexican courts. Compliance requires a Mexican tax ID (RFC) for registration, irrespective of residency status.

Investment trends emphasize rental yields from platforms like Airbnb, with gross returns of 5-8% in high-demand zones like Zona Romantica and Marina Vallarta, supported by year-round tourism but vulnerable to seasonal dips and platform regulations. Appreciation has averaged 10-15% annually pre-2025, though 2025 forecasts predict moderation to 5-7% amid economic headwinds like U.S. interest rates and Mexico’s inflation. Diversification appeals to investors hedging against domestic markets, yet risks include hurricane exposure, title disputes from informal land histories, and local opposition to overdevelopment straining water resources. Data from multiple realty reports indicate sustained foreign interest despite cooling, with active listings up 18% to 628 houses by June 2025.

Diversification Efforts and Vulnerabilities

Puerto Vallarta’s economy remains overwhelmingly dominated by tourism and related services, which constituted approximately 81% of employment in the tertiary sector as of 2010, with primary sectors like agriculture and fishing accounting for only 1.34% and secondary sectors for 15.21%. Efforts to diversify have focused on bolstering agriculture in rural outskirts such as Las Palmas, Ixtapa, and Boca de Tomatlán, where production centers on tropical fruits like bananas, mangoes, and soursops, alongside vegetables including tomatoes, chili peppers, and squash. Local initiatives include promoting organic products through markets and fairs, developing agrotourism via orchard visits and cooking workshops, and investing in sustainable irrigation to enhance food self-sufficiency and rural employment, though these remain secondary to tourism and lack quantified economic impact data.

Artisanal fishing persists as a subsistence activity in Bahía de Banderas, with fishers employing diversified labor including agriculture, but it contributes minimally to overall GDP amid declining stocks and environmental pressures. Recent municipal strategies amid a 2025 tourism slowdown have emphasized niche expansions within tourism, such as cultural, culinary, medical, and eco-tourism, alongside infrastructure upgrades and partnerships, rather than developing independent sectors like manufacturing or technology. Academic analyses recommend government and private initiatives to foster broader diversification, citing risks of overreliance on tourism revenues, yet implementation has been limited, with agriculture and fishing retaining marginal roles.

This tourism dependence exposes the local economy to significant vulnerabilities, including external shocks that disrupt visitor flows; for instance, the COVID-19 pandemic halted operations, with recovery projected to take up to five years due to the absence of alternative revenue streams. In 2025, a sharp decline in U.S. air arrivals, Puerto Vallarta’s primary market has led to reduced bookings, thinner margins for hotels, restaurants, and operators, and broader economic strain, underscoring fragility to geopolitical tensions, economic downturns in source markets, and seasonal fluctuations. Natural hazards, such as hurricanes, further amplify risks, as contingency planning remains tourism-centric, with limited buffers from diversified industries.

Infrastructure and Transportation

Airport Developments and Connectivity

Licenciado Gustavo Díaz Ordaz International Airport (PVR), located 7.5 kilometers north of downtown Puerto Vallarta, serves as the primary gateway for the region’s tourism-driven economy, handling both domestic and international flights under the operation of Grupo Aeroportuario del Pacífico (GAP). The facility features a single terminal currently divided into domestic and international sections, with a runway capable of accommodating wide-body aircraft.

Passenger traffic at PVR reached approximately 6.72 million in 2023, increasing slightly to 6.80 million in 2024, reflecting steady demand primarily from leisure travelers despite minor fluctuations in domestic arrivals.[116] From January to October 2024, the airport processed 2.35 million domestic passengers and 3.17 million international passengers, underscoring its reliance on foreign visitors for growth. These figures, driven by seasonal peaks in winter months, have necessitated infrastructure upgrades to alleviate congestion and support projected expansions in tourism arrivals.

A major expansion project, initiated in 2022 with an investment exceeding 9.2 billion pesos (about $187 million USD), aims to construct a new Terminal 2, adding over 74,000 square meters of space and doubling the airport’s overall capacity to handle up to 12 million passengers annually. As of August 2025, construction stood at 54% completion, incorporating additional boarding gates, advanced security screening, and energy-efficient designs, with phased operations expected to commence in late 2026.

This initiative forms part of GAP’s broader $2.5 billion investment plan through 2029 across its network, prioritizing Puerto Vallarta to accommodate rising international traffic amid Mexico’s post-pandemic aviation recovery.

Connectivity at PVR emphasizes non-stop routes to North American hubs, with 17 airlines operating services to around 50 destinations, predominantly in the United States and Canada. U.S. carriers such as Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, Delta Air Lines, Frontier Airlines, Southwest Airlines, United Airlines, and others provide year-round and seasonal flights from cities like Los Angeles, Dallas, Chicago, and Houston, facilitating direct access for the bulk of American tourists. Canadian connectivity is robust via Air Canada, WestJet, Sunwing, and Air Transat, with WestJet alone linking to 12 airports during peak winter seasons from hubs including Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, and Edmonton. Domestic Mexican routes are served by Aeroméxico, Volaris, and VivaAerobus to Mexico City, Guadalajara, and other cities, though international flights account for over 70% of traffic volume. Limited European service exists, primarily seasonal charters, highlighting PVR’s orientation toward North American markets tied to vacation packages and cruise passenger feeders.

Road Networks and Regional Links

Puerto Vallarta’s internal road network consists of urban arterials such as Avenida Francisco Medina Ascencio and the Libramiento Luis Donaldo Colosio, which serves as a partial bypass to manage through-traffic and reduce congestion in the downtown core. These roads connect key zones including the hotel district, Marina Vallarta, and the Malecón boardwalk, though rapid urbanization has led to frequent bottlenecks, particularly during peak tourist seasons. Recent municipal upgrades, including the reconstruction of Francisco Murguía Street initiated in early 2025, aim to improve intersections with State Highway 544 for smoother access to peripheral areas.

Regionally, Federal Highway 200 forms the backbone of coastal connectivity, extending northward from Puerto Vallarta through Riviera Nayarit to destinations like Bucerías and Punta Mita, and southward along the Pacific toward Costalegre and Manzanillo. Improvements to this highway, including widening of narrow, winding segments north of the city, have addressed historical accident hotspots, though daytime driving remains recommended due to occasional hazards. The recent inauguration of the final stretch of the Jala-Puerto Vallarta highway in December 2024 further streamlines northern links by integrating with Highway 200 and providing direct access from inland Nayarit routes.

Inland access to Guadalajara, Jalisco’s capital, was transformed by the full completion of the Guadalajara-Puerto Vallarta toll highway in December 2024 after 13 years of construction, spanning over 86 kilometers with 45 bridges, three tunnels, and seven interchanges to cut travel time from 4-4.5 hours to approximately 2.5 hours. This route also facilitates connections to Tepic in Nayarit via intermediate segments like Compostela-Las Varas, opened in March 2024. Complementary projects, such as the 30% complete rehabilitation of Highway 544 as of August 2025, enhance secondary links to mountainous inland municipalities including Mascota and San Sebastián del Oeste, supporting ecotourism and local commerce.

Maritime Facilities and Cruise Operations

Puerto Vallarta’s primary maritime facilities consist of the downtown cruise terminal and Marina Vallarta, supporting both commercial cruise operations and private yachting. The cruise terminal features three docking berths along the city’s deep-water harbor shoreline, enabling the simultaneous accommodation of multiple large vessels. A new cruise terminal was inaugurated in the summer of 2020 to enhance passenger processing and services. Marina Vallarta, located north of the city center, provides 354 slips for yachts up to 160 feet in length, equipped with utilities including 100-480 amp power, water, pump-out services, fuel, and high-speed Wi-Fi.

Cruise operations have shown steady growth, with the port handling 76 ship calls and 237,000 passengers in the first four months of 2025 alone, marking a 12% increase in arrivals compared to 2024 and generating over 412 million pesos in economic impact. In 2023, the port welcomed 112 international cruises carrying more than 350,000 passengers. Earlier data from 2018 recorded 134 ship visits with 328,800 passengers, while 2019 schedules anticipated 180 calls. Passenger spending averaged $83.90 per person during the first four months of 2024, contributing to local commerce near the terminal.

These facilities position Puerto Vallarta as a key stop on Mexican Riviera itineraries, primarily serving lines from the United States and connecting to destinations like Cabo San Lucas and Mazatlán. Operations emphasize efficient turnaround for day visits, with tenders used when necessary for larger ships, though most vessels dock directly due to the harbor’s configuration. Marina Vallarta supports year-round yachting tourism, including haul-out and repair services, complementing the cruise-focused infrastructure.

Governance and Public Services

Local Government Structure and Policies

Puerto Vallarta’s municipal government adheres to the standard structure for Mexican municipalities, as defined by the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States and the Organic Municipal Law of Jalisco, featuring an ayuntamiento composed of a presidente municipal (mayor), 13 regidores (councillors divided into commissions), and one síndico municipal (auditor) elected every three years by plurality vote. The ayuntamiento holds legislative authority over local ordinances, budgets, and oversight of the executive, while the mayor directs administrative operations through a cabinet of departments such as urban planning, public works, finance, and tourism promotion. The municipal presidency is housed in the historic City Hall (La Presidencia) in the Centro district, serving as the administrative hub.

Luis Ernesto Munguía González of the Partido Verde Ecologista de México (PVEM) has served as presidente municipal since October 2024, leading the 2024-2027 administration with a focus on revitalizing infrastructure and public services following electoral promises of enhanced cleanliness and safety. His tenure has encountered challenges, including a reported approval rating drop to below 30% by mid-2025 amid resident complaints over inadequate waste collection, starting with only 10 functional vehicles inherited—and perceived fund mismanagement, prompting emergency repairs to roads and sanitation systems.

Key policies under this administration center on the approved Municipal Development and Governance Plan 2024-2027, which guides resource allocation toward sustainable tourism management, environmental protection, and urban renewal, including extensions to the Malecón boardwalk and Avenida México stormwater improvements. A parallel Sustainability Plan targets reducing ecological strain from rapid visitor growth, incorporating land-use regulations via the Local Ecological Planning Program to balance development with natural preservation. To address tourism-driven pressures, the city council has proposed a 1-3% tax on short-term rental platforms like Airbnb to generate revenue for strained infrastructure, reflecting efforts to mitigate over-reliance on visitor spending amid rising local costs.Additional initiatives include a Cultural Program promoting local artists and heritage preservation, alongside social welfare supports like family aid programs coordinated with state authorities. These measures aim to foster inclusive growth, though implementation faces scrutiny over execution efficacy and fiscal transparency.

Public Health, Water, and Waste Management Issues

Puerto Vallarta experiences recurrent public health challenges, primarily from vector-borne diseases exacerbated by seasonal rainfall, inadequate drainage, and urban expansion. Dengue fever, transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes breeding in standing water, has surged regionally, with Jalisco state reporting a significant increase in cases during 2024, prompting intensified fumigation efforts in Puerto Vallarta where over 9,000 blocks were sprayed by June 2025 to curb outbreaks during the rainy season. Local authorities noted approximately 250 dengue cases in the area ahead of the official 2024 season, with infections persisting into winter months due to residual mosquito populations. Water scarcity heightens risks of waterborne illnesses like cholera and typhoid, as highlighted in 2023 assessments linking shortages to potential bacterial proliferation in contaminated sources, though cholera remains low-risk nationally with no recent local outbreaks reported by health monitors. Other respiratory threats, including rising COVID-19 cases in the region as of early 2025 and a national whooping cough outbreak claiming 56 infant lives by mid-2025, underscore vulnerabilities in densely populated tourist zones, where tourism-driven population influx strains healthcare access.

Water supply in Puerto Vallarta faces chronic shortages, intensified by dry seasons, El Niño effects reducing 2024 rainfall, and climate variability depleting aquifers. A 2025 INEGI resident survey revealed widespread frustration with inconsistent supply, public transport, and infrastructure, attributing issues to rapid urbanization outpacing reservoir replenishment and distribution networks. City officials projected stabilization of the drinking water system by late September 2025 following drought mitigation, but experts warn of ongoing stress, with proposals for seawater desalination to address peak dry-season deficits when precipitation drops sharply. Quality concerns arise from potential contamination during shortages, prompting reliance on bottled water and cisterns, while broader Mexican water plans note over 35 million citizens, including coastal areas, lacking reliable access amid per capita availability declines.

Can You Drink Puerto Vallarta Tap Water https://promovisionpv.com/can-you-drink-puerto-vallarta-tap-water/

Waste management and sewage systems struggle under tourism pressures, leading to pollution incidents and inadequate treatment. Raw sewage leaks onto beaches like Playa Los Muertos were documented in June 2025, traced to a local hotel and prompting demands for accountability from business owners concerned over public health and tourism impacts. Drainage failures, such as a persistent leak near Constitución and 5 de Febrero streets in July 2025, have channeled polluted wastewater into urban areas, highlighting aging infrastructure unable to handle expanded loads from new developments. Municipal initiatives include enhanced garbage collection programs launched in September 2025 with by-appointment bulky waste pickup and recycling routes for plastics, glass, and metals operating weekdays to foster separation and reduce landfill strain. However, unchecked building booms risk collapsing sewage and refuse networks, as excess construction without proportional upgrades exacerbates overflows and environmental degradation, including microplastic accumulation on Pacific beaches from upstream waste sources.

Crime, Safety Perceptions, and Security Measures

Puerto Vallarta experiences lower violent crime rates compared to other parts of Jalisco state, with a homicide rate of 9.1 per 100,000 residents as of 2025, significantly below the national average and concentrated outside tourist zones. Property crimes, including residential burglary and auto theft, constitute about 34% of incidents, while violent offenses like robbery and assault primarily affect locals in peripheral areas rather than visitors.[50] In 2023, reported homicides numbered 19, robberies around 200, and total common law crimes approximately 5,000, reflecting a stable but persistent petty crime presence driven by opportunistic theft in crowded areas.

Public perceptions of safety in Puerto Vallarta have fluctuated, with the percentage of residents reporting feelings of insecurity rising from 19.4% to 30.5% between early and late 2024, though it stabilized at 24.7% feeling unsafe by September 2025, ranking the city 8th safest in Mexico. Tourists generally view the destination as secure, with crowdsourced data indicating moderate concerns over vehicle theft (35.6%) and physical attacks (24.4%), lower than in nearby Guadalajara where overall crime levels are rated high at 73%. The U.S. State Department classifies Jalisco as Level 3 (“Reconsider Travel”) due to crime and kidnapping risks statewide, but imposes no restrictions on Puerto Vallarta or Riviera Nayarit, attributing relative safety to cartel avoidance of revenue-generating tourist hubs.

Local authorities have implemented targeted security measures, including the “Tourist Button” initiative launched in January 2025, which enables rapid emergency response via a dedicated app or hotline for visitors facing threats. Enhanced police patrols in the hotel zone and boardwalk areas, coupled with surveillance in high-traffic districts, aim to deter petty crime, though broader cartel-related violence in Jalisco underscores vulnerabilities beyond municipal control. These efforts prioritize tourism protection, as disruptions could economically isolate the city, but residents note uneven enforcement in non-tourist neighborhoods.

Culture and Attractions

Landmarks and Architectural Highlights

The Parish of Our Lady of Guadalupe serves as Puerto Vallarta’s principal architectural landmark, located in the historic center adjacent to the main square. Construction foundations were laid in 1903, with the first mass held in 1921 after initial completion, though work halted in 1929 due to economic challenges. The main tower was finished in 1955, topped by a concrete crown added in 1963 and designed by José Esteban Ramírez Guareño, while the facade was completed in 1987. Its design blends Neoclassical elements with Baroque influences, featuring a cruciform layout, Corinthian and Ionic orders, and a distinctive crown evoking European regal motifs.

The Malecón boardwalk along the waterfront hosts a prominent collection of public sculptures installed progressively since the 1990s, enhancing the area’s architectural and artistic profile. Notable examples include “The Boy on the Seahorse” (El Caballito del Mar), a bronze statue depicting a child riding a seahorse, which has become an iconic photo spot. Other highlights comprise “The Lovers,” portraying actors Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton from the 1964 film The Night of the Iguana; the “Rotunda of the Sea,” featuring 16 bronze pieces including monumental and smaller forms; and works like “Millennia” by Mathis Lidice and “Origin and Destiny” by Pedro Tello. These sculptures, crafted in bronze, stone, and other durable materials by Mexican artists, number over a dozen and reflect themes of marine life, human figures, and local culture.

Puerto Vallarta’s historic core exhibits traditional Mexican colonial architecture adapted to the coastal environment, characterized by whitewashed adobe or stucco walls, red clay-tile roofs, and wrought-iron balconies. This “Vallarta style,” influenced by post-1960s tourism growth, incorporates narrow vertical windows and small balconies for ventilation and shade, as seen in neighborhoods like Gringo Gulch with its colorful facades. Additional structures include the Municipal Palace near the main square and the El Faro Lighthouse, a modern addition symbolizing maritime heritage.

Beaches, Outdoor Activities, and Ecotourism

Puerto Vallarta’s beaches line the Bahía de Banderas, with varying characteristics suited to different preferences. Playa de los Muertos, situated in the central Zona Romántica district, spans approximately 1 kilometer of golden sand and serves as a hub for swimming, sunbathing, and access to beachfront vendors, though it experiences higher foot traffic due to its urban location. Conchas Chinas Beach, to the south, features rocky outcrops interspersed with sandy pockets, clearer waters ideal for snorkeling, and fewer crowds, attracting visitors seeking quieter coastal exploration. Playa Camarones, near the city center, holds Blue Flag certification for its maintained water quality, calm seas, and emphasis on environmental standards, including waste management and accessibility. Further south, Playa Mismaloya and Playa Las Gemelas offer rugged terrains backed by jungle foothills, better for boat access and less development.

Outdoor pursuits leverage the region’s Sierra Madre Occidental slopes and Pacific waters. Snorkeling and scuba diving predominate at offshore sites, with visibility often reaching 20-30 meters in calmer months. Zip-lining courses, such as those in the surrounding tropical canopy, span up to 2 kilometers across multiple lines, combining aerial views with jungle immersion. ATV tours navigate dirt trails through forested areas, typically lasting 3-4 hours and including stops at waterfalls or tequila distilleries. Hiking options include paths to elevated viewpoints like the Cross Trail, offering panoramas of the bay and ascending roughly 300 meters in elevation. Whale watching tours operate seasonally from December 8 to March 23, focusing on humpback migrations in Banderas Bay, with regulations limiting boat approaches to 60 meters from pods to minimize disturbance.

Ecotourism emphasizes protected zones preserving biodiversity amid tourism pressures. The Los Arcos National Marine Park, encompassing granite arches and islets 11 kilometers south of downtown, safeguards coral reefs, sea caves, and habitats for over 200 fish species, sea turtles, and rays; access is regulated via permitted boats to curb overfishing and anchoring damage. Kayaking and stand-up paddleboarding here allow low-impact exploration of arches rising up to 30 meters from the sea. Inland, the Vallarta Botanical Gardens cover 40 hectares of conserved rainforest, featuring orchid exhibits, river trails, and ex-situ preservation of endemic plants, drawing visitors for guided nature walks that highlight reforestation efforts. Mangrove ecosystems along the Cuale River support birdwatching for species like herons and egrets, with eco-tours promoting non-invasive observation to maintain wetland filtration functions. These sites underscore causal links between habitat integrity and sustained visitation, though official data indicate ongoing challenges from plastic debris and unregulated charters.

Festivals, Media Influence, and Cultural Events

Puerto Vallarta’s transformation into a global tourist destination was significantly propelled by mid-20th-century Hollywood productions. The 1963 filming of John Huston’s The Night of the Iguana, starring Richard Burton and Ava Gardner, with Elizabeth Taylor frequently visiting the set, drew international media coverage and celebrity attention to the then-obscure fishing village, catalyzing infrastructure development and visitor influxes that reshaped its economy from agrarian roots to tourism-dependent. This cinematic exposure, amplified by subsequent films and ongoing promotional campaigns involving media outlets and influencers, has sustained Puerto Vallarta’s image as a romantic, bohemian paradise, though critics note it sometimes overshadows local socioeconomic challenges in favor of idealized portrayals benefiting the hospitality sector.

Did you know about the Movies Shot in Puerto Vallarta? https://promovisionpv.com/did-you-know-about-the-movies-shot-in-puerto-vallarta/

beverly hills chihuahua, blind side, herbie goes banana, Jalisco, le magnifique, limitless, lost in the bermuda triangle, man friday, Mexico, movies filmed in puerto vallarta, night of the iguana, predator ,puerto vallarta ,puerto vallarta movie set, puerto vallarta movies, puerto vallarta squize, revenge, sharktopuss, undown, the domino principle, wich way por favor,

The city hosts numerous annual festivals rooted in Catholic traditions and modern tourism appeals. The Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, spanning December 1 to 12, features massive processions, live mariachi performances, fireworks, and street fairs honoring Mexico’s patron saint, drawing over 100,000 participants and visitors to venues like the Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish. Fiestas Patrias celebrations on September 16 commemorate Mexican Independence with El Grito reenactments, parades, traditional foods like chiles en nogada, and mariachi music across the Malecón boardwalk. Día de los Muertos observances in late October to early November include altars, calaveras parades, and beachside vigils blending indigenous and Catholic elements, attracting cultural tourists.

Contemporary cultural events emphasize culinary, artistic, and LGBTQ+ themes, reflecting the city’s evolving demographic. The Festival Gourmet Internacional, held annually in May, showcases over 50 chefs from Mexico and abroad with tastings, wine pairings, and beachfront demonstrations, generating substantial economic impact through ticketed events. Vallarta Pride in early May features parades, parties, and beach events in the Zona Romántica, celebrating queer culture since 2002 and drawing thousands amid Mexico’s broader Pride movements. Weekly art walks in the Romantic Zone, typically Thursdays from November to May, involve gallery openings, live music, and street performances, fostering a vibrant scene influenced by expat artists and local craftspeople. Neighborhood patron saint festivals, varying by community throughout the year, preserve huichol indigenous influences through dances, altars, and feasts, though commercialization has intensified post-media boom.

Neighborhoods and Social Fabric

Zona Romantica and Central Districts

The Zona Romántica, also designated as the Romantic Zone or Viejo Vallarta (Old Town), encompasses the southern segment of Puerto Vallarta’s historic core, situated south of the Río Cuale and including neighborhoods like Emiliano Zapata. This area features narrow cobblestone streets lined with boutique shops, cafes, and restaurants, preserving much of the city’s early 20th-century architecture amid a bohemian atmosphere that attracts tourists and expatriates. Key landmarks include Playa Los Muertos, a primary beachfront extending from the Los Muertos Pier, and adjacent zones like Olas Altas and Conchas Chinas, which have anchored traditional tourism since the mid-20th century.

El Centro, the central downtown district, lies immediately north of the Río Cuale along the Malecón boardwalk, forming the waterfront hub with early cultural institutions, hotels, and religious sites such as the Parish Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe, constructed in the 1910s. This zone supports pedestrian-oriented commerce, including markets and galleries, and serves as a convergence point for locals and visitors, with the Malecón facilitating events and daily promenades. Together, these districts embody Puerto Vallarta’s transition from a fishing village officially established as a municipality in 1918, to a tourism-driven economy post-1960s infrastructure expansions, though rapid visitor influx has intensified local-tourist mixing and property value pressures.

Socially, Zona Romántica hosts a diverse expatriate community, including retirees and seasonal residents drawn to its affordability relative to northern hotel zones and vibrant nightlife, which activates after sunset with bars and inclusive venues catering to varied demographics. El Centro maintains a more balanced resident-tourist fabric, with markets like Mercado Municipal reflecting everyday Mexican commerce alongside tourist-oriented stalls. Urban development in these areas emphasizes preservation amid growth; for instance, 2025 initiatives include Malecón extensions with updated lighting and irrigation, while broader plans address overcrowding through mobility enhancements like bike shares, reflecting causal pressures from tourism comprising over 80% of local GDP as of recent estimates. No specific demographic breakdowns for these micro-areas exist in census data, but Puerto Vallarta’s overall 2020 population of 291,839 shows near gender parity (50.1% male), with service sector employment dominating. Challenges include seasonal gentrification, where rising rentals displace lower-income locals, though enforcement of historic zoning limits high-rise intrusions compared to peripheral expansions.

Northern Expansions and Suburban Areas

Marina Vallarta represents the primary northern expansion of Puerto Vallarta, developed as a master-planned community in the mid-1980s on former marshland north of the city center. Construction of its 450-slip yacht marina commenced in 1986 under the direction of the Martínez Güitrón brothers, reaching operational capacity by 1990 and catalyzing luxury residential, hotel, and commercial growth. The area features high-end condominiums, resorts like the Camino Real, golf facilities, and waterfront promenades, drawing international investors and boosting local tourism infrastructure with over 1,200 berths today. This development shifted Puerto Vallarta’s urban focus northward, emphasizing upscale amenities over traditional fishing village roots.

Suburban neighborhoods adjacent to Marina Vallarta, such as Versalles and Fluvial Vallarta, have emerged as residential hubs for families, expats, and professionals seeking quieter alternatives to downtown. Versalles, a flat, pedestrian-friendly zone established as a post-1970s suburb, integrates single-family homes, mid-rise apartments, and commercial strips with wide streets and green spaces; its proximity to the Licenciado Gustavo Díaz Ordaz International Airport (3 km away) and emerging gastronomic scene have driven population growth and property values, with average home prices rising 15-20% annually since 2020. Fluvial Vallarta complements this with modern planned layouts, emphasizing infrastructure like parks and connectivity to major arterials, appealing to middle-class commuters.

The 5 de Diciembre colonia, positioned immediately north of the Río Cuale, functions as a transitional suburban area with historic cobblestone streets, local markets, and direct beach access via Playa Camarones. Developed in the early 20th century but expanded post-1960s tourism boom, it houses a mix of modest homes, new condos, and community anchors like the Parroquia de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, fostering a blend of Mexican local life and expat residency; its lower density and walkability to the Malecón (1-2 km) make it attractive for long-term residents avoiding high tourist density. These northern suburbs reflect Puerto Vallarta’s broader urban evolution, with residential expansion fueled by foreign investment and infrastructure upgrades, including Malecón extensions approved in 2025 to enhance connectivity; however, growth has strained local resources, prompting municipal plans for sustainable zoning to mitigate sprawl.

Southern and Peripheral Communities

The southern communities of Puerto Vallarta lie along the South Shore, where the Sierra Madre Occidental foothills descend to the Pacific coast, forming a rugged landscape of cliffs, coves, and beaches distinct from the more developed central districts. This region begins south of Conchas Chinas and extends to Boca de Tomatlán, encompassing villages that historically relied on fishing and subsistence agriculture before tourism’s expansion.

Mismaloya, situated about 10 kilometers south of downtown Puerto Vallarta, originated as a small fishing settlement with roots tracing to pre-Columbian times in the Xalisco kingdom around 600 BC, though modern development accelerated after serving as a primary filming location for John Huston’s 1963 movie The Night of the Iguana, which drew international attention and catalyzed Puerto Vallarta’s tourism boom. The village features a 300-meter sandy beach with calm waters suitable for swimming and sunbathing, supported by local eateries specializing in seafood like ceviche. Adjacent to Los Arcos National Marine Park, it attracts snorkelers and divers to underwater rock formations and marine life, while luxury resorts have emerged alongside traditional homes, blending exclusivity with natural seclusion.

Boca de Tomatlán, roughly 18 kilometers south via Highway 200, functions as a modest fishing village at the Horcones River’s estuary, with a population centered on small-scale fishing and boat operations for tourist excursions to nearby hidden beaches. Its 200-meter beach offers gentle waves and a short malecón ideal for observing sunsets, with amenities limited to beachside restaurants serving fresh catches rather than large commercial developments. As a gateway for water taxis to sites like Las Ánimas, the community experiences seasonal influxes of day-trippers, yet maintains a quieter, less urbanized character compared to northern expansions.

More peripheral settlements like Yelapa, reachable only by a 45-minute boat ride from Boca de Tomatlán, preserve a semi-isolated communal structure established around 1870 by four founding families, where descendants of original Huichol-influenced inhabitants retain collective land control, resisting large-scale commercialization. This village of approximately 1,000 residents features a palm-fringed beach for kayaking and fishing, inland waterfalls such as Colomitos, and eco-focused tourism emphasizing homestays and local cuisine over high-rise infrastructure. Economic activities center on sustainable fishing, horseback tours through jungle trails, and small artisan markets, fostering a social fabric rooted in tradition amid growing visitor interest.

All About Puerto Vallarta https://promovisionpv.com/all-about-puerto-vallarta/

Puerto Vallarta is not about perfection, it is about connection. At PromovisionPV.com, our goal is to help travelers avoid generic experiences and discover the city as it truly exists.

PromovisionPV.com Ranks #1 Travel Guide vs … https://promovisionpv.com/promovisionpv-com-travel-guide-ranks-1-vs/

Puerto Vallarta Advertise & Be Seen ! https://promovisionpv.com/puerto-vallarta-advertize-be-seen/

We provide information and resources for visitors to Puerto Vallarta, areas of The Riviera Nayarit and other destinations in both states of Jalisco and Nayarit . You will find variety of content, including articles, blog posts, videos, photos, descriptions and interviews, all of which are designed to help visitors plan their trip, including attractions, restaurants, and events. Follow: https://promovisionpv.com/

Visit and Subscribe to our YouTube Channel for more Puerto Vallarta – Riviera Nayarit 220+ videos: Subscribe: https://www.youtube.com/@promovision/videos

Puerto Vallarta – Riviera Nayarit Archives 2024 Follow: https://promovisionpv.com/puerto-vallarta-nayarit-archives-2024/ Over 1,000 pages: Somethings you may not know about Puerto Vallarta, Riviera Nayarit and Mexico archives puerto vallarta, arts, bucerias, cirque du soleil, costa alegre, culture, destination wedding, events, events schedule, gastronomy, gay pv, gay vallarta, informations, insurance, Jalisco, lgbtq, medical care, mexican food, Nayarit, news, Nuevo Nayarit, Punta Mita, Rincon de Guayabitos, safety, San Blas, San Pancho, Sayulita, tourism, tours, travel, travel blog, travel guide, travel tips, wedding, YouTube videos, attractions, beaches, blog,

Follow: Web site: https://promovisionpv.com

Subscribe: YouTube: https://youtube.com/promovision/videos

Subscribe: Instagram: https://instagram.com/promovisionpv/

Follow: LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ray-dion-48861926/

Follow: X: https://x.com/promovisionpv

Follow: Threads: https://www.threads.net/@promovisionpv

Follow: Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61576061534287

Follow: Blue Sky Social: https://bsky.app/profile/promovision.bsky.social

Promote Your Tourism Business, Restaurant, or Tour Puerto Vallarta on PromovisionPV.com https://promovisionpv.com/promote-your-tourism-business-restaurant-or-tour-puerto-vallarta-on-promovisionpv-com/